Category Archives: Upward mobility

October 26, 2011 How is Celebrity Related to Social Mobility?

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Sociology, Upward mobility, Video

March 29, 2011 Fame: Be Careful What You Wish For

Want to be famous? The weathered cliché “be careful what you wish for” is particularly salient in the era of YouTube, where uploading a video can lead to international recognition. Instant stardom is possible, but so is instant infamy.

You have probably heard about two recent examples, one where a student posted a rant about Asian students at her university, and another by thirteen-year-old Rebecca Black, whose music video went viral after many called it the worst song ever.

We probably know people who share angry thoughts about various ethnic groups and went to middle school with kids who thought they were talented singers (or actors, athletes, poets, or artists….). But fortunately for those of us who came of age before YouTube, any fallout from our peers was limited in scale. People might have made fun of others behind their backs (remember a few years ago when concerns about gossiping cliques reigned in the headlines?), but now the internet means that anyone with a computer can contribute their insults.

And yet Rebecca Black has been able to get media coverage any newcomer would kill for. She has been on The Tonight Show and apparently has a record deal. But one would image all of the hateful comments she has received online—which I choose not to repeat here—would be hard for anyone to handle, especially a thirteen-year-old who had not been in the public eye before.

Before the internet, the doors to fame were guarded by gatekeepers: agents, managers, casting directors, A&R reps, and editors to name a few. Talented people who failed to get the approval of these gatekeepers would find themselves on the outside, with few options other than to keep trying to impress the gatekeepers. And hateful comments would likely be limited to letters, handled by editors, a studio or agent, and maybe the occasional obscene phone call, resolved by changing one’s number.

The gatekeepers aren’t gone, but the entrances to fame (and infamy) are more porous today. We can go around them—sometimes at our peril, and sometimes without even meaning to. And the critics no longer need a byline to express their disapproval.

In Celebrity Culture and the American Dream I write about how the internet age offers more “jobs” in the fame industry, but not all of these jobs pay well, if anything. Stories about those who found fame via the internet, like Justin Bieber, help promote the idea of limitless upward mobility at a time when the economy stagnates, and the gap between the wealthiest Americans and the rest of us widens.

In fact, one wonders if the infamous—like the student who posted her rant about Asians—will face serious economic setbacks in the future due to the notoriety a single video created. Whether we like it or not, in the internet age we are all public figures.

Tags: celebrity, fame, infamy, internet, justin bieber, karen sternheimer, rebecca black, youtube

- Leave a comment

- Posted under Internet, Upward mobility

March 22, 2011 Are Celebrities Just Like Us?

In my research of fan magazines dating back a century, one of the central tensions in celebrity coverage has been whether celebrities are really “just like us” or uniquely different. Are they mortals or demigods?

In some respects, being famous sets one apart by virtue of definition: in Celebrity Culture and the American Dream, I define celebrity as “anyone who is watched, noticed, and known by a critical mass of strangers” (p. 2). This is purposely a broad definition, since celebrities can (and do) exist within smaller groups and may remain largely unknown in other groups, but still enjoy the benefits of limited celebrity status.

In fan magazines throughout history, celebrities have been regarded as special, important, and worthy of public attention. That makes them different from the collective “us,” obviously.

They seem to lead  magical lives at times, and many can afford a lifestyle only available for the wealthiest earners. As the story “Struggling Along on $50,000 a Year” (at right) from the February 1928 issue of Motion Picture Classic sarcastically notes, celebrities had to make do with just enough to pay their servants, buy mansions, and maintain their fabulous wardrobes. (According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, $50,000 is the equivalent of nearly $650,000 in 2011 dollars).

magical lives at times, and many can afford a lifestyle only available for the wealthiest earners. As the story “Struggling Along on $50,000 a Year” (at right) from the February 1928 issue of Motion Picture Classic sarcastically notes, celebrities had to make do with just enough to pay their servants, buy mansions, and maintain their fabulous wardrobes. (According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, $50,000 is the equivalent of nearly $650,000 in 2011 dollars).

And yet this “just like us” theme persists. In the earliest fan magazines, this theme meant to reassure readers that “picture players” were morally upright in a time when the movies and their performers were often viewed with suspicion.

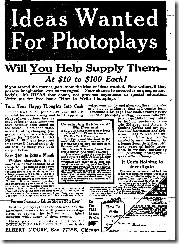

As movies gained legitimacy, fan magazines let readers know that the new movie industry represented economic opportunity, and that success was right around the corner. As in this ad below—from the February 1916 issue of Motion Picture Classic—readers were invited to write and act in the movies and earn their fortune too.

was right around the corner. As in this ad below—from the February 1916 issue of Motion Picture Classic—readers were invited to write and act in the movies and earn their fortune too.

Today the suggestion that we too can make it big is more subtle, but it is still here. Rather than an ad asking readers to write a screenplay, the “just like us” paparazzi shots of a celebrity shopping or taking a child to school reminds readers that celebrities are mere mortals, and not so far removed from everyone else. If they can make it, maybe we can too. And if they experienced dramatic upward mobility in their rise to stardom, perhaps it is proof that the rags-to-riches story is not just a fairy tale.

Tags: celebrity, celebrity culture, just like us, karen sternheimer, upward mobility

- Leave a comment

- Posted under History, Upward mobility

March 15, 2011 Celebrity and Royalty

During a recent radio interview I was asked a great question: why are Americans interested in British royalty, since they represent the antithesis of democracy?

Certainly the British are more interested in their royal family than we are, as gossip about its members get intense coverage even without an impending royal wedding. Although we claimed independence from the British 235 years ago, we still enjoy some of their pop culture like The Office, Pop Idol (or American Idol as we know it), and even Antiques Roadshow.

As I write about in Celebrity Culture and the American Dream, American celebrity coverage has changed quite a bit over the last century, but one element is pretty consistent. Celebrities seem to embody proof that we can all rise to the top, become fabulously wealthy and admired. In my research of fan magazines from the 1910s to the present, that message was threaded throughout both fan magazine articles and ads.

But there are contradictions here too. While some magazines have features that insist celebrities are “just like us,” their wealth and fame make them profoundly different from everyone else.

Sure, they might be humble and down-to-earth individually, but fans sometimes presume stars have magical qualities and feel honored or even overcome with emotion to be in their presence. Something like getting to meet an actual prince or princess.

In some ways, coverage of celebrities bears much resemblance to coverage of the British royal family. We can peak behind the scenes and see how the privileged live, then bask in their problems and feel better about our status as commoners.

A royal wedding not only allows observers to vicariously bask in the mass consumption, but it represents an opening into an otherwise closed status. Marrying a prince is the ultimate fairy tale of upward mobility. Becoming a celebrity seems like the next best thing if becoming royalty is not an option.

But sometimes the illusion that anyone can make it big shatters. Rather than looking critically at the illusion, we tend to target our disappointment at celebrities themselves.

In a recent Los Angeles Times op-ed, Neal Gabler argues that part of the reason Charlie Sheen received so much negative attention was because his behavior challenged the idea that celebrities are just like us:

Entertain us, and we’ll grant you fame, riches and adoration — so long as you remain one of us. Violate that contract at the peril of your career. Abide by it, like, say, Tom Hanks, and you will be rewarded with longevity. All we ask is that you be, or at least appear to be, normal.

Sheen’s openness about his life of excess reminds us that he is not everyman, Gabler notes.

And yet part of the pleasure of following celebrities—and royals’—lives is bound in their apparent ordinary extraordinariness. They are human, but at the same time deified by virtue of the public’s interest. And they serve as great characters in our never-ending real-life soap opera, excess and all.

Tags: celebrity, karen sternheimer, neal gabler, royal wedding, sociology

- Leave a comment

- Posted under History, Scandals, Upward mobility